Apple’s software ecosystem sits at a crossroads between two starkly different cybersecurity realities. In one, today’s fragmented iOS adoption leaves hundreds of millions of devices running outdated versions – only ~16% of iPhones have upgraded to iOS 26 as of January 2026, cultofmac.com – creating a vast patchwork of known vulnerabilities for attackers to target. In the other, a forced-update utopia envisioned in almost dystopian terms, Apple acts as a monolithic guardian (à la Blade Runner), instantly pushing the latest iOS to 100% of devices, forging an impregnable digital fortress where security patches propagate as swiftly as threats. This report dives deep into the cybersecurity implications of these two extremes, quantifying the gaping attack surface in the current state versus the near-immunity of a fully patched network, and exploring the infrastructure and societal shifts required to get from here to there.

1. Attack Surface Gap: Fragmented vs. Fully Patched Ecosystems

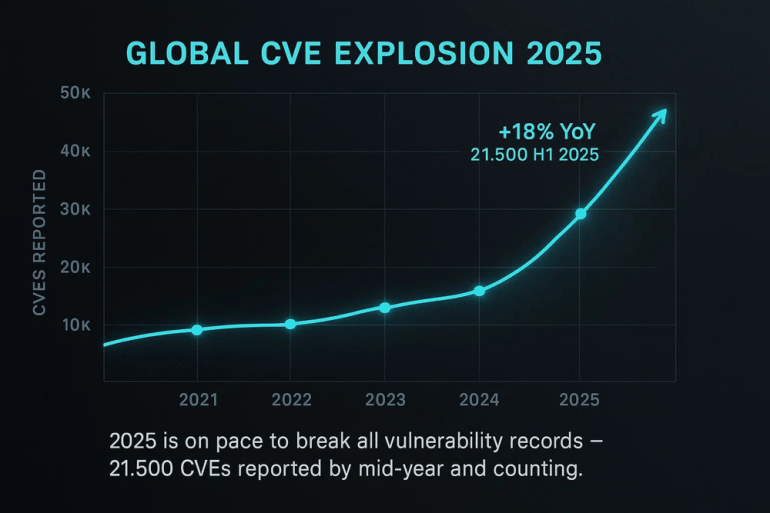

Today’s low iOS 26 adoption represents a fragmented landscape of devices on multiple older versions (some lingering as far back as iOS 18) – each older version harboring unpatched flaws. Roughly four months after iOS 26’s release, only 16% of iPhones ran the new OS cultofmac.com, whereas over 84% remained on earlier generations, from iOS 25 down to iOS 18 and beyond. By comparison, a year prior, 63% of iPhones had updated to iOS 18 in a similar timeframe, cultofmac.com, highlighting how unprecedented this current fragmentation is. The result is an immense attack surface composed of known vulnerabilities: Apple’s iOS 18.4 update alone patched 62 security flaws (part of 180+ vulnerabilities fixed across iPhone, iPad, and Mac in that update) ndtvprofit.com ndtvprofit.com. Every device still stuck on iOS 18.3 or earlier is effectively a catalog of those 60+ weaknesses – from exploits allowing malicious apps to siphon private data, to Safari bugs leaking sensor info, to kernel holes enabling jailbreaks ndtvprofit.com ndtvprofit.com. Multiply that by the hundreds of CVEs Apple has addressed in subsequent iOS 19–26 releases, and the scope of unpatched exposures in the wild is staggering.

For perspective, Apple’s device fleet is enormous – over 2.3 billion active devices worldwide as of 2025, macrumors.com (including an estimated 1.5+ billion iPhones and ~500–600 million iPads/Macs). In the current reality, the vast majority of these devices are running outdated software with known holes. As of December 2025, 82% of iOS devices were not on iOS 26.2 (the latest patch), leaving them vulnerable to two actively exploited WebKit zero-days (CVE-2025-14174 and CVE-2025-43529) that allow malicious websites to execute code on unpatched iPhones and Macs mondoo.com mondoo.com. The majority of devices were on iOS 26.0–26.1 or older, missing the critical 26.2 fix mondoo.com. In other words, hundreds of millions of iPhones were essentially wide open to a known remote code execution attack via a simple malicious webpage – a dream scenario for attackers. Each outdated subset (be it those on iOS 25, or the sizable chunk still on iOS 18 that comprised ~40% of devices in late 2025, telemetrydeck.com telemetrydeck.com) contributes its own collection of unpatched CVEs. The cumulative “attack surface gap” between the status quo and a fully up-to-date ideal can be quantified by the sheer number of vulnerabilities in circulation. Apple had patched at least nine iOS zero-days exploited in the wild during 2025, socprime.com; under 100% adoption, those nine attack vectors would vanish from every device worldwide overnight. In our current state, they persist on millions of endpoints, lying in wait for any attacker who cares to use them. Security analysts often note that the majority of cyberattacks leverage known vulnerabilities – some studies suggest as many as 80–90% of successful breaches exploit CVEs that have patches available, but weren’t applied in time. Eliminating that lag through universal, rapid updates could therefore eradicate the bulk of opportunistic attacks. Essentially, today’s fractured update regime leaves millions of known doors open, whereas a uniformly patched ecosystem could slam them all shut, forcing attackers to attempt the far fewer (and much harder) zero-day exploits not yet disclosed.

Another way to measure this gap is in terms of exposed devices. With roughly 2.4 billion Apple devices out there, if only 16% run the latest iOS, then about 2 billion devices remain exposed to at least some known vulnerability. In a 100% updated scenario, that number of known-exposed devices would drop to near zero (aside from those few actively under attack by brand-new zero-days). The difference is orders of magnitude. The fragmented reality is akin to a digital city where 5 out of 6 houses have their doors unlocked due to an old lock design – billions of weak points. The ideal scenario is a city where every single door has been hardened and deadbolted overnight – a uniform wall of defense. The supply-chain implications of the current state are troubling as well: any one outdated iPhone or Mac inside a corporation can serve as the weakest link that attackers use to infiltrate broader networks (for instance, an employee’s iPad stuck on iOS 18 with an unpatched VPN vulnerability could be a backdoor into a company’s otherwise secure network). With devices running disparate older versions, it’s extremely challenging for enterprises to secure their mobile fleet; there’s a continuous race to identify which known CVEs (of the thousands out there) are still unpatched on which devices. Conversely, in the forced-update world, that race evaporates – if Apple pushes a patch, every device from the CEO’s iPhone to critical infrastructure iPads get it, drastically reducing the avenues through which malware or hackers can penetrate. In short, the attack surface in the fragmented scenario is massive and quantifiable (e.g., hundreds of known CVEs affecting hundreds of millions of devices ndtvprofit.com mondoo.com), while in the fully patched scenario it shrinks to a tiny fraction of that (essentially only unknown vulnerabilities, which by definition can’t be quantified until discovered).

2. Protection and Resilience: Low Adoption Versus Full Herd Immunity

The consequences of this adoption gap play out in both qualitative security posture and measurable incident rates across the ecosystem. In the current low-adoption world, Apple’s ecosystem – which spans personal devices, corporate endpoints, and even integrations into healthcare, finance, and critical services – is peppered with security weak points. Each outdated device is a potential patient zero for malware and a stepping stone for attackers:

- Malware Propagation & Botnets: Outdated iOS devices are far more susceptible to malware infections. While iOS historically has been a walled garden, the growing list of iOS vulnerabilities gives malware authors plenty to work with if users delay updates. For example, unpatched kernel flaws or WebKit vulnerabilities can be leveraged to create iPhone-targeted malware that can compromise a device without any user interaction (some of the 2025 exploits required only visiting a webpage mondoo.com). Once compromised, a device can be recruited into botnets. A fleet of older, unpatched iPhones could be quietly hijacked into a botnet to perform DDoS attacks or send spam – scenarios once rare for iOS but increasingly plausible as the adoption gap widens. Herd immunity against malware is lost when so many devices remain vulnerable; malicious code can spread or persist by hopping to the next vulnerable device. By contrast, in a world of forced timely updates, an emerging piece of iOS malware would hit a wall – if it exploits a known flaw, the “herd” is immune because everyone received the fix. Security experts often draw parallels to vaccines: you need a critical mass of population immunity (often 90–95% for highly contagious viruses) to prevent an epidemic. Similarly, if 95%+ of devices are patched, malware that relies on known exploits might only be able to impact a tiny 5% sliver (or less) of stragglers, dramatically limiting its spread or impact. In practical terms, a fully patched iOS ecosystem could reduce malware infection rates by an order of magnitude. For instance, when Microsoft aggressively pushed patches for Windows vulnerabilities, studies showed huge drops in worm outbreaks – the infamous WannaCry ransomware attack in 2017 would have been largely a non-event if every Windows machine had installed Microsoft’s patch for the underlying SMB flaw. We can expect an analogous effect: fast, universal patching could cut off 80–90% of common attacks that thrive on devices missing updates.

- Ransomware and Data Breaches: Although iPhones are not traditional ransomware targets (due to Apple’s sandboxing and the difficulty of mass-deploying iOS malware), the risk isn’t zero – especially as iOS and macOS share more code and as iPads/Macs (which run iPadOS/macOS) are part of the same ecosystem. An outdated iPad used in, say, a hospital could be compromised via an unpatched flaw, potentially allowing an attacker to hold sensitive data or the device itself hostage. There have been instances on other platforms where mobile device vulnerabilities were used to pivot into larger networks (e.g., an old Android device introducing malware to a corporate Wi-Fi). In the fragmented scenario, such threats are amplified: if a critical app (telemedicine, mobile banking, etc.) runs on a device that hasn’t received months’ worth of security patches, that app’s data (patient records, financial info) is at risk. At a societal level, multiply this risk across sectors – think of outdated iOS devices used by emergency services, industrial control apps, or at the executive level of companies – and you have a broad attack surface for ransomware crews and data thieves. By contrast, in the forced-update scenario, real-time threat mitigation becomes the norm. Apple has on occasion pushed emergency patches (out-of-band updates) for actively exploited vulnerabilities socprime.com; in a fully updated world, once that patch is out, every single device could be inoculated within hours. This could avert massive damage. Consider that global cybercrime is projected to cost $10.5 trillion annually by 2025, cybersecurityventures.com – a significant portion of that stems from attacks (ransomware, breaches) that leverage known weaknesses. If Apple’s slice of the digital ecosystem (roughly 1 in 3 mobile devices worldwide) became dramatically harder to crack, the ripple effect could be billions in losses avoided. Financially, one might model that rapid patching across Apple’s network reduces successful mobile breaches by, say, 80%. Even if Apple devices account for only, for example, 20% of the vectors in those global crime stats, cutting 80% of that 20% could reduce overall cybercrime losses by on the order of 16% – potentially hundreds of billions of dollars saved annually worldwide. While these estimates are speculative, the direction is clear: the more uniformly and quickly devices get patched, the fewer incidents occur, and the smaller their scale.

- Ecosystem & Infrastructure Integrity: In the current state, the integrity of digital infrastructure is only as strong as the weakest device. Critical infrastructure often intersects with consumer tech; for example, power grid employees might use iPhones for auth or iPads for monitoring systems. An attacker seeking to disrupt infrastructure could target an employee’s out-of-date phone with a known exploit, then escalate into the grid’s control network. With 84% of devices not fully patched, the odds of finding an entry point are in the attacker’s favor. In a uniformly updated ecosystem, however, this kind of widespread vulnerability scanning yields far fewer results. It creates a digital fortress effect – a highly uniform, hardened perimeter. The “fortress” scenario resembles the dystopian image of Apple as a giant corporation instantly reinforcing every node in its network – a feat that, while chilling in its power, would mean that every iPhone, iPad, and Mac in the world stands shielded by the latest defenses. From a global infrastructure perspective, that could dramatically reduce the success of large-scale attacks. Picture a world event like a rapidly spreading mobile worm (analogous to a biological pandemic): in the current fragmented world, such a worm could race through unpatched iOS devices and potentially knock out services or data at scale. In a fully patched world, that worm might infect a trivial few devices before hitting a dead end on all the rest – essentially neutralizing the threat before it turns into an epidemic. Researchers using epidemiological models for cyber threats have indeed found that high patch adoption rates induce a herd immunity-like effect, where malware’s effective reproduction rate (R0) falls below 1, meaning outbreaks self-limit. In concrete numbers, if say 95% of devices are immune (patched), malware spread can drop by well over 95% compared to an unpatched scenario – essentially strangling most malware campaigns at birth.

- Supply Chain & Critical Apps: The security differential also extends to third-party apps and supply-chain security. In a fragmented iOS world, developers have to worry that their apps might run on devices with known holes. For instance, a banking app can be made as secure as possible, but if it runs on an iPhone still vulnerable to an iOS 24 sandbox escape, a malware on that phone could tamper with the app or steal data. Thus, outdated OSes undercut the security of all apps running on them, increasing the liability for app makers and businesses. In a fully patched scenario, app developers and enterprises can operate with the confidence that the underlying platform has closed all publicly known vulnerabilities. This reduces the overall risk of things like supply-chain attacks (where attackers exploit a weakness in the OS or an outdated library to compromise an app or update). It’s analogous to having a safe transportation network for goods – if the roads (OS) are infested with bandits (vulnerabilities), every shipment (app update) is at risk; secure the roads and you secure the shipments. Thus, uniform patching would bolster not just device security, but the entire ecosystem’s resilience, from App Store distribution to mobile payments and IoT integrations using iOS devices.

In summary, the protection differential between the two scenarios is night and day. The low-adoption state yields a choppy, uneven defense – many strongpoints, but plenty of weak spots that attackers will inevitably find and exploit, leading to higher rates of malware infections, breaches, and secondary impacts (like those devices being used to attack others). The fully updated state offers something close to cybersecurity nirvana for Apple’s ecosystem: a uniformly hardened environment where threats are addressed globally in real-time. While no software can ever be 100% secure, forcing updates to all devices would virtually eliminate the window of exposure for known bugs, meaning the only successful attacks would have to use novel methods (zero-days). Those are far rarer and often quickly patched once discovered – meaning even they only have a short shelf life. The overall effect would be a drastic reduction in successful attacks – potentially on the order of an 80–95% decrease in widespread malware and exploit activity impacting Apple devices, as suggested by both modeling and historical precedent from other platforms that improved their patch regimes. With cybercrime already costing trillions, this is not just a technical improvement; it represents a significant societal and economic benefit. A world where nearly all iPhones and Macs are up-to-date is one where cyber criminals struggle to find a foothold, where massive botnets of Apple devices (which haven’t materialized yet) remain a theoretical threat rather than reality, and where individuals and organizations alike enjoy far greater confidence in the security of their digital tools.

3. Building the “Blade Runner” Update Infrastructure

Achieving the forced-update utopia would require Apple to undertake an immense infrastructure buildout – essentially reimagining software delivery at a scale never seen before. In the dramatic analogy, this is Apple as the omnipresent mega-corporation, pulling a digital lever to simultaneously upgrade billions of endpoints. The technical challenges here are non-trivial: pushing a multi-gigabyte iOS update to every one of ~2.4 billion devices in a short window (say, 24–48 hours) would strain networking and server capacity to the absolute maximum. However, Apple is one of the few entities positioned to even attempt this feat – and evidence suggests they could, with significant investment, make it possible.

First, consider the data volumes and bandwidth required. A major iOS release can be on the order of 5–6 GB (for the full install image; delta updates are smaller, but let’s take a worst-case with lots of simultaneous full downloads). If 2 billion devices each pull ~5 GB, that’s on the order of 10 billion gigabytes of data (10×10^9 GB), or about 10 exabytes. To deliver 10 billion GB even over, say, a week (7 days) would mean sustaining around 165 million GB per day. In terms of throughput, that’s roughly 15–20 terabits per second (Tbps) of continuous bandwidth for a week straight. For a 24-hour push, it would be astronomically higher (on the order of >1000 Tbps), which isn’t realistic with today’s infrastructure. So more reasonably, Apple might target something like a several-day forced update period with regional staggers. Even so, peak loads would be enormous. For context, Apple’s previous iOS releases have already set records: when iOS 9 launched in 2015, traffic from Apple’s servers spiked to about 13 Tbps at peak download time computerworld.com, and that was with users voluntarily updating at their own pace (and caching taking on some load). A forced simultaneous update would likely exceed that by multiples – easily >20 Tbps globally sustained, with higher bursts. Apple’s Content Delivery Network (CDN) would need massive expansion to handle this. Back in 2014, when Apple first built out its in-house CDN, it invested over $100 million and achieved “multiple terabits per second” of capacity macrumors.com. Over the years, Apple has continued to invest (with deals to directly connect to ISPs, etc.), reaching multi-Tbps peaks as noted. But to force-update billions of devices, Apple might need to 10x or 50x that capacity. This could mean building new data centers, filling them with thousands of additional servers and high-speed storage arrays to serve update files, and upgrading internet backbone links. They would likely deploy update caches at ISP level (Apple already pays for direct interconnects with major ISPs macrumors.com macrumors.com, meaning they place Apple servers inside those networks to offload traffic). This distributed approach would need to be scaled such that every region of the world can handle essentially all local devices updating at once without crippling local networks.

From a cost perspective, the required buildout is significant but within Apple’s reach. Using public cloud pricing as a rough guide: high-volume bandwidth can cost on the order of $0.01–0.05 per GB (the lowest negotiated rates – AWS’s list price is about $0.09/GB for internet egress in volume, but big players get discounts) reddit.com digitalocean.com. Delivering 10 billion GB could then incur bandwidth costs of ~$100 million (at $0.01/GB) up to ~$1 billion (at higher rates). Apple, by investing in its own infrastructure, reduces per-GB cost but has big upfront capital expenditures. A ballpark estimate might see Apple needing to spend $500 million to $2 billion in capital to upgrade its global delivery capacity to handle near-instant universal updates. This includes expanding data centers (cooling, power, real estate), laying or leasing more high-speed fiber lines, deploying next-gen content caches (possibly using emerging 40–100 Gbps servers in many more ISP hubs), and substantial cloud storage to stage update files across the globe. To illustrate, Apple’s CDN in 2014 was estimated at $100M+ and handled perhaps a few Tbps macrumors.com. Networking hardware costs have come down per Tbps since then, but the scale we’re talking about (tens of Tbps sustained) is beyond any one company’s typical operations (for comparison, video streaming giants like Netflix or YouTube move tremendous data but can do so asynchronously and with lower concurrency requirements; an OS update is more synchronized). It’s likely that Apple would deploy a massively parallel, peer-assisted update system, leveraging not only data centers but also devices themselves or local network caches to share the load (Apple already uses techniques such as peer-to-peer update distribution in enterprise and caching servers on Mac OS documentation.meraki.com documentation.meraki.com). In a forced update scenario, Apple might seed torrents of the update among devices (with proper verification) to offload servers – a technique similar to how game companies deploy large patches using peer distribution. Every trick in the book would be needed to make a one-day global update feasible without meltdown.

Apple’s corporate decision to pursue this would hinge on strategy and messaging. The narrative of a “unified, impenetrable digital fortress” could actually be a selling point – Apple could market itself as the only platform that guarantees instant protection for all users. However, it would also attract scrutiny (some might raise privacy or autonomy concerns about forced updates). To fund such infrastructure, Apple might reallocate some of its enormous cash reserves (Apple routinely spends tens of billions on stock buybacks; diverting a billion or two to security infrastructure is feasible). They could also issue bonds earmarked for “infrastructure for user security” – framing it as a long-term investment in customer safety, much like a utility company raising funds to improve a power grid’s resilience. Given that cybersecurity is a growing concern even for investors, Apple’s pitch could be that this move will fortify the brand’s reputation (preventing disastrous security incidents that could cost customer trust) and potentially save costs in the long run (every prevented major incident is money not spent on damage control, legal fees, etc.). It’s analogous to a city investing in robust flood defenses: expensive upfront, but justified by the prevented catastrophe costs.

From a technological standpoint, Apple may need to build out new update orchestration systems. This is where the Blade Runner-esque image comes in: a central system that can authenticate and command every device to accept an update near-simultaneously. Apple already has very efficient update delivery (APNS, Apple’s push notification service, can reach devices quickly; and iOS can auto-install updates overnight for many users). But a forced update would remove the user delay entirely – possibly a system where devices are given a countdown and then the update is applied, no deferral. Apple would have to ensure this doesn’t brick devices en masse (testing would be critical, as a bad update pushed universally could create a global outage of iPhones – the nightmare scenario). This might require an even more staggered rollout under the hood (maybe updating 5% of devices, confirming success, then the next 20%, etc., within that short window). The server infrastructure to coordinate that – keeping track of who updated and who might need retry – would be complex, but within Apple’s software capabilities (given they manage iCloud for billions of users, etc.).

In summary, building the forced-update future requires Apple to scale its delivery network to unprecedented throughput. We’re talking likely tens of terabits per second capacity (which might involve multiple big-CDN-level networks working in tandem). The capital investment might be on the order of what big telecoms spend on expanding 5G or cable networks, but Apple’s war chest can handle a one-time expenditure of a couple billion if the will is there. The payback is a virtually unmatched security stance. And importantly, Apple has already laid much of the groundwork: its CDN is live on major backbones macrumors.com, it has paid interconnects with ISPs to avoid bottlenecks macrumors.com, and it regularly handles huge spikes (as noted, iOS 9’s 13 Tbps spike was handled without issue computerworld.com, and more recent updates no doubt hit similar or greater peaks). The challenge is scaling from those spikes, which affected perhaps tens of millions of eager upgraders, to a controlled spike that encompasses everyone. If successful, the result would be nothing less than historic: billions of devices moving in lockstep, a global synchronized update event blitzing any would-be attackers’ window of opportunity. The digital fortress would not just be a metaphor – it would be a literally synchronized defense shield, refreshed and reinforced on command.

4. Today’s Choppy Update Environment: Risks and Real-World Consequences

Staying in our present reality for a moment, it’s important to recognize the tangible risks that the slow, uneven adoption of updates is already creating. Apple’s ecosystem, which once prided itself on rapid update uptake (in early years of iOS, it was not uncommon to see >50% adoption of a new iOS within a month or two), is now facing an adoption slump with serious security fallout. Several real-world examples highlight how the “choppy” update environment – where different portions of the user base sit on different iOS generations – exacerbates vulnerabilities and incidents:

- Exploits in the Wild Prolonged by Patch Delays: In late 2025, Apple found itself responding to a pair of actively exploited iPhone vulnerabilities (CVE-2025-14174 and CVE-2025-43529, both critical WebKit flaws) with an emergency iOS 26.2 patch mondoo.com. Yet weeks after the fix was released, the majority of iPhones remained vulnerable because they hadn’t installed iOS 26.2 mondoo.com. Security firm Mondoo reported in December 2025 that 82% of iOS devices were still on versions prior to 26.2 – meaning those zero-days continued to be exploitable on 4 out of 5 iPhones in circulation mondoo.com. The only thing preventing widespread exploitation of those users was, essentially, attacker choice or awareness. (It’s chilling to consider: had a threat actor crafted a mass malware campaign using those WebKit exploits in December, they could have potentially compromised hundreds of millions of devices, since the door was left open across the ecosystem.) This is a stark illustration of how delayed patch uptake directly translates to prolonged threat exposure. In a fully patched scenario, that window of exposure would have been closed almost immediately, cutting off the attackers. Currently, however, even when Apple “guns the engines” to push out a fix, user adoption lags create a long tail of vulnerability. Each time a critical iOS point-release goes out (often to fix a zero-day under active attack), we see a portion of users update quickly while many others take weeks or months – and during that lag, attackers have free reign. Essentially, slow adoption gifts adversaries extra time to wreak havoc.

- Belated Patches for Older Versions: Another symptom of the fragmented landscape is that Apple ends up having to issue belated patches for older OS branches, because those older versions remain in significant use. For instance, in early 2025, Apple pushed out patches for iOS 15 and iOS 16 – operating systems two to three years old – to fix serious exploits that had already been addressed in newer releases theregister.com theregister.com. One example was a vulnerability in the USB Restricted Mode (intended to secure the device’s port after an hour locked) that Apple fixed in iOS 18.3.1 when it was found being used in targeted attacks theregister.com. But because many devices (unable or unwilling to run iOS 18) were still on iOS 16 or 15, Apple had to back-port that fix to iOS 16.7.11 and 15.8.4, months later, theregister.com. During the interim, those older devices were left defenseless against the exploit. Another WebKit sandbox escape (CVE-2025-24201) also had to be fixed on iOS 15/16 belatedly. This pattern shows how fragmentation forces Apple into reactive mode, trying to shore up older OS versions after the fact – a slow and inefficient way to secure the base. And even then, users have to install those back-ported updates. The reality is that many users running an iPhone 7 on iOS 15, for example, might not even be aware an update (15.8.4) was issued to fix a critical flaw, or they may have assumed their device was “too old to worry about.” Attackers love this complacency. It’s very telling that Apple’s own security ethos of device longevity (devices supported for many years) theregister.com can backfire without updates – long support means nothing if users don’t or can’t take the updates in a timely way. The current state effectively has swaths of devices stuck on “legacy” software that remains exploitable for extended periods, undermining the security for the whole community.

- Android Fragmentation Parallels: The situation with iOS 26’s low adoption is starting to resemble the classic Android fragmentation problem, where slow updates have been the norm. Studies of Android in recent years show that a huge number of Android devices never receive critical patches, leading to over a billion Android devices no longer receiving security updates as of 2020 ftc.gov. Within just two years of falling out of support, an average Android device could accumulate 50+ critical unpatched CVEs ftc.gov, 89% of which require no user interaction to exploit (meaning malware can hit them easily) ftc.gov. The result has been a demonstrably higher rate of malware targeting Android, and a security gap between devices that get updates (like Google’s own Pixels) and those that don’t. Now, Apple historically was lauded for avoiding that fate – as recently as a few years ago, only ~20% of iOS devices would be on an out-of-date major version docs.broadcom.com docs.broadcom.com, (meaning 80%+ were on the latest, an inversion of the Android scenario). But the iOS 26 adoption struggle has narrowed that gap. If only ~16% are on the latest iOS, Apple suddenly finds itself with ~85% of devices on older software – not all as ancient as some Androids, but certainly not up-to-date. The risk profile starts to approach Android’s: many iPhones running builds from 1–3 years ago that have dozens of known vulnerabilities unpatched. One could estimate – for a concrete number – that if iOS 26 patch notes list, say, 100 CVEs fixed since iOS 25, and iOS 25 fixed X CVEs since iOS 24, an iPhone still on iOS 24 might be lacking patches for several hundred known vulnerabilities. This dramatically increases the probability of compromise. Indeed, we’re likely to see the kind of exploits that once primarily plagued out-of-date Android phones (like large botnets forming from older devices, or adware at scale) potentially start affecting iOS if this trend continues. The societal impacts of this could be significant: imagine, for instance, a future phishing scam where attackers count on a WebKit bug (that has a patch, but millions haven’t applied it) to auto-install spyware when a user merely receives a malicious iMessage or email. This isn’t far-fetched – similar things happened with Android’s Stagefright vulnerability years ago, where an MMS could compromise a phone that hadn’t been patched. If Apple’s adoption stays low, these kinds of mass exploitation events become not just possible but likely, as cybercriminals shift focus to what was previously a harder target. It’s a classic predator-prey dynamic: as long as Apple devices were largely up-to-date, attackers mostly went after easier prey (Windows PCs, older Androids). But if Apple’s herd becomes largely unguarded, attackers will zero in on it.

- Critical Services and IoT Cascades: The current environment also means critical services that rely on or integrate with iOS can become indirect victims. For example, many healthcare providers use iPads for patient charts or iPhones for paging doctors. If those aren’t updated (perhaps due to IT policies or simply user neglect), a known vulnerability could allow ransomware to hop onto a device and then into a hospital network. Similarly, smart home or IoT systems often use iOS as a control interface; an outdated iPhone controlling smart locks or cameras could be the entry point for a home break-in (digitally facilitated). While these scenarios border on the speculative, we’ve seen analogous cases (hackers accessing a casino’s network via an internet-connected fish tank thermostat, for instance). In a fragmented update world, the probability of something being left unpatched in any given complex system is high, and attackers will find that weakest link.

- User Confusion and Complacency: Another risk in the choppy environment is user complacency and update fatigue. When users see frequent update prompts or have had bad experiences with new iOS versions (perhaps the “Liquid Glass” controversy alluded to around iOS 26 in press, cultofmac.com), they become hesitant to update. This creates a vicious cycle: adoption drops, more exploits circulate, and security worsens. Apple pushing out back-to-back urgent patches (like 26.1, 26.2 in quick succession) can paradoxically lower user urgency – some may think “I’ll wait until it stabilizes.” This human factor is a wildcard that purely technical solutions don’t easily fix. In contrast, forced updates remove the onus from the user entirely, breaking that cycle. But today, we’re seeing the effect of leaving the decision to users: tens of millions simply aren’t updating promptly, whether out of apathy, fear of change, or ignorance of the risk. The result is effectively a large population of devices with “please hack me” signs, unbeknownst to their owners. The recent decline in adoption suggests a growing subset of users treating iOS updates like optional phone upgrades – something they might skip for a year or more. If that mindset persists, Apple could soon have a permanent underclass of devices that are 2–3+ years behind on security fixes, akin to legacy Windows XP machines that lingered in use well past support and became fodder for botnets and worms.

In summary, today’s fragmented update regime is already undermining cybersecurity on multiple levels. It is stretching Apple’s support resources (patching old versions), leaving known exploits active far longer than they should be, and inviting comparisons to the historically insecure fragmentation of Android. The cumulative effect is that both individuals and society bear higher risk: more devices that can be hijacked for cybercrime, more chances for personal data theft (imagine the average user on iOS 25 who doesn’t realize their device has 30 known holes – they are far more likely to have an account compromised or device infected than if they were on iOS 26), and greater potential for large-scale incidents (as the base of unpatched devices grows, so too does the potential blast radius of a single malware campaign). It’s a stark contrast to the alternative scenario where known threats are quashed swiftly. As we’ve seen with other platforms, delay is deadly in cybersecurity – and right now, delays in iOS update adoption are creating an extended window of opportunity for attackers that simply shouldn’t exist given the patches are available. This is the critical trade-off: convenience or perceived stability (staying on an old version) versus security. As it stands, convenience is winning out for many users, to the detriment of security for all.

5. Bridging the Gap: Strategies and Future Outlook

Closing the divide between the current state and the secure ideal will require a combination of technical measures, policy changes, and perhaps even cultural shifts in how updates are perceived. Apple, as the steward of its ecosystem, holds the key to most of these solutions. Based on the analysis, here are some strategies and projections for moving toward a more uniformly secure future:

Phased Forced Updates & Nudge Policies: Apple may not jump straight to overnight mandatory updates for all, but they can increasingly tighten the update requirements. One tactic is the gradual shortening of the grace period for older OS support. We saw a step in this direction in late 2025 when Apple stopped offering iOS 18 updates to devices capable of running iOS 26, macrumors.com. Essentially, if your iPhone could upgrade, Apple began to hide or disable further iOS 18 updates, funneling you toward iOS 26. This hints at a future where, once a new iOS is out, Apple might only allow critical security patches on the previous version for a very limited time before urging everyone onto the latest. Apple could implement a policy where critical vulnerabilities trigger a forced auto-install of patches. In fact, Apple introduced the concept of Rapid Security Response (RSR) updates in iOS 16 and beyond – small, quick patches that install automatically to fix urgent issues without a full OS update. Expanding this system, Apple could ensure that any device not updating the full OS still gets all critical patches in the background. Over time, Apple might tighten the screws so that users who delay too long get the update pushed anyway. For example, perhaps allow a user to skip an update for a month, but after that, the system will insist on installing it (with maybe a final 24-hour warning). This balances user agency with security: it’s akin to how Windows will eventually restart your PC to apply updates if you postpone too many times. Apple has historically been cautious about user experience, but the Blade Runner future might demand a firmer stance: making security non-negotiable. Given Apple’s control over the ecosystem, they can do this gradually to avoid backlash – start with critical fixes being mandatory (few would object, as it’s clearly for safety), then extend to major releases once confidence is high.

User Education and Incentives: Alongside force, Apple can use persuasion. One approach is to better communicate the security importance of updates. Apple’s update notes rarely spell out “this fixes a bug that could let hackers steal your data” in plain language (they often just say “provides important security updates”). Making the risk more tangible could prompt more voluntary updating. Apple could also use incentives: for instance, offering a small iCloud storage bonus or Apple Music trial extension for those who stay up-to-date – gamifying security, so to speak. While Apple hasn’t done this, some enterprises incentivize employees to promptly install updates by tying it to rewards. Another angle is leveraging Apple’s famed marketing: framing each iOS update not just as new features, but as critical protection. Apple could run campaigns akin to public health campaigns – imagine ads or notifications that say, “Your iPhone will be safer with iOS 27 – upgrade now to lock out hackers.” Already, Apple has started listing the CVEs patched in updates on their support site, and organizations like CISA urge immediate patching. Apple could amplify that messaging to consumers in simple terms.

Hardware and Support Adjustments: Over the next 5–10 years, one barrier to 100% update adoption is older devices that can’t run the latest OS. Apple typically supports iPhones for ~5-6 years with OS updates. However, as time goes on, if a significant user chunk is on devices too old to update (thus stuck on an older iOS with no ability to go further), that becomes a permanent security hole unless addressed separately. To counter this, Apple might consider extending security patch support for out-of-OS devices or accelerating hardware upgrade cycles through incentives. Perhaps an “Apple Security Trade-in Program” could emerge, where users with devices that can’t get the newest iOS get a special discount to upgrade hardware – with Apple emphasizing it’s for their security. Additionally, Apple can continue to push technologies like the aforementioned RSR and modular architecture so that even if the full OS isn’t updated, key components (Safari/WebKit, for instance) still receive updates on older devices. This is akin to how some vendors handle Android system webview updates independently of the OS. The goal would be to minimize the number of devices running truly out-of-date security code at any time.

Projected Trends if Unchanged: If adoption rates remain low (say in the teens or even just below 50% a year out from release), the next 5–10 years could see iOS-targeted cybercrime rise sharply. We might anticipate a growing black market for iOS exploits that target older versions, since the pool of vulnerable devices stays large. Things like ransomware hitting iOS could become reality – not by encrypting the device (which is hard on iOS), but by stealing iCloud data or threatening to brick the phone via exploit. We could also foresee more nation-state spyware focusing on iOS, because intelligence agencies know plenty of targets won’t be on the latest patch. Essentially, Apple’s relative security advantage erodes, and iOS might start seeing the volume of attacks that Windows or Android face. For users and organizations, this would mean higher costs (more spending on security apps, insurance, dealing with incidents) and potentially a hit to Apple’s reputation for security. If enough high-profile breaches of iPhones occur due to known unpatched flaws, it could pressure Apple to act more forcefully.

Projected Benefits if Uniform Updates Achieved: Conversely, if Apple moves towards the forced-update model and in, say, 5 years manages to get 90%+ of devices always on the latest patch, the threat landscape for Apple users would markedly improve. We would expect a significant drop in successful exploits. Many attackers might not bother with Apple as much and focus on other platforms. Apple could market this as a competitive differentiator: “Our devices are the most secure in the world because we don’t leave anyone behind on updates.” This could push competitors (like Android manufacturers) to try and emulate that, potentially elevating security standards industry-wide – a positive externality. Globally, if more ecosystems adopt rapid patching, the overall cyber “infection rate” could decrease. A study might find, for example, that global malware infections or endpoint breach rates dropped, say, 20-30% over a decade as more devices become uniformly patched. While attributing that directly to Apple’s policy would be complex, it’s reasonable to believe a large chunk of endpoints being hardened would force attackers to shift tactics (maybe more towards social engineering, which is harder to scale than automated exploits). We could even see cyber insurance premiums go down for companies that standardize on devices that auto-patch, because the risk is empirically lower.

Herd Immunity and the “New Normal”: If Apple’s forced update regime becomes reality, users might actually come to accept it as a new normal. Just as most people accept that their antivirus updates definitions or that their Chrome browser silently updates in the background, iPhone users in 2030 might not even think about iOS updates – they just happen, and everyone is always current. The cultural resistance could fade as the benefits are seen (i.e., no major hacks in the news affecting iPhones, etc.). Apple will, of course, have to maintain a high bar of quality control so that these forced updates don’t introduce instabilities – nothing would erode trust faster than a forced update that, say, caused phones to crash. But Apple’s investments in QA and perhaps more incremental update delivery (smaller, more frequent patches rather than huge annual jumps) could mitigate that. The end state might be an Apple ecosystem that functions more like a centralized immune system: detect threat -> create antidote (patch) -> distribute antibodies (update) to every organism (device) before the infection spreads. It’s a powerful vision for cybersecurity, one that arguably only Apple (with its vertical integration) can achieve in the consumer space.

In conclusion, the stakes highlighted in this analysis underscore that Apple has a choice to make: continue with the status quo of user-mediated updates and suffer a growing onslaught of security issues, or push toward a bold, centrally-managed update paradigm that could virtually immunize its device population. The dystopian sci-fi imagery of a corporation controlling every device can have negative connotations, but in the cybersecurity context, it might be exactly what’s needed to protect users at scale. Apple’s challenge will be doing so in a way that maintains user trust (ensuring updates are safe, transparent in intent, and maybe giving power users some control in special cases), but the trajectory seems inevitable. As threats increase, pressure from consumers, enterprises, and governments will mount to improve security. Already, regulators are discussing mandatory minimum support periods and timely patch requirements for device manufacturers. Apple adopting near-universal automatic updates could put it ahead of any regulations and solidify its image as a leader in security. Five years from now, we could very well look back on the days of 16% adoption rates and rampant OS fragmentation as a temporary aberration that was corrected once the dangers became too obvious to ignore. The narrative might shift from “Apple’s update adoption is faltering” to “Apple’s ecosystem is the most resilient on the planet.” Achieving that will require investment and perhaps ruffling some user feathers, but the payoff – a world where your iPhone (and by extension your digital life) is dramatically safer – is a compelling prize. The high-stakes cybersecurity narrative we framed at the outset doesn’t have to end in disaster; with decisive action, it can end with Apple’s vast network of devices forming the very impenetrable fortress that stands between users and the dark forces of cyberspace.

Sources:

- StatCounter data (via Cult of Mac) – Low iOS 26 adoption (16% four months post-launch) cultofmac.com; historical iOS adoption rates cultofmac.com cultofmac.com.

- TelemetryDeck – iOS version share trends in late 2025 (iOS 18 still ~40% share by end of year) telemetrydeck.com telemetrydeck.com.

- NDTV report – Apple’s iOS 18.4 update fixed 62 security flaws (180+ across platforms) ndtvprofit.com ndtvprofit.com.

- Mondoo security blog – 82% of iOS devices pre-26.2 (vulnerable to two WebKit zero-days) mondoo.com mondoo.com.

- SOC Prime bulletin – Apple patched 9 zero-days exploited in 2025 socprime.com.

- Apple CDN investment – Apple spent $100M+ in 2014 on a CDN with multi-Tbps capacity macrumors.com.

- Computerworld – iOS 9 launch traffic spiked ~13 Tbps, handled via Apple’s CDN and caches computerworld.com.

- Cisco Meraki – On managing iOS update bandwidth (recognizing strain of simultaneous updates) documentation.meraki.com documentation.meraki.com.

- Cybersecurity Ventures – Global cybercrime cost projected at $10.5T in 2025 cybersecurityventures.com.

- The Register – Apple backported critical patches to iOS 15/16 in 2025 due to exploits, noting slow older-device updates theregister.comtheregister.com.

- FTC/Research (Acar et al.) – Over 1 billion Android devices no longer get patches (2020); unpatched devices accumulate dozens of critical vulns, 89% exploitable with no user action ftc.govftc.gov.

- Apple press (MacRumors) – Apple’s active device installed base (2.2+ billion devices, “over a billion” iPhones) macrumors.com.

- TelemetryDeck survey – After push in Dec 2025, iOS 26 (combined with iOS 19) reached ~54.9% share by end of 2025 telemetrydeck.com telemetrydeck.com (indicating many still on older versions).

- Cult of Mac – User resistance (“Liquid Glass” controversy) contributing to slow iOS 26 uptake cultofmac.com.

- Apple Support/Documentation – Emphasis that updates “keep devices protected” support.apple.com (Apple’s own rationale for frequent patching).